I had dreamt of visiting the North Sea island of Helgoland since my early years as a birder. Last year, I became aware of a bird observatory on the island and a little research soon revealed that they welcome volunteers to assist with ringing, counting, as well as other work around the observatory. This sounded like an ideal opportunity and after getting a positive response to my application, the month of September was booked for volunteering at the “Vogelwarte Helgoland”. Although many consider October to be the most exciting time to visit Helgoland, the autumn migration season is already in full swing in September. The month was indeed fantastic, with a number of very special birds and a very fun and interesting time with the other people at the observatory. I am dividing my time on Helgoland into two posts of two weeks each (read the second post here).

On my way to Helgoland from Bonn, where I live since having finished my BSc in Maastricht in June, I stayed at Hotel Hohenzollernhof in Cuxhaven, a simple but very suitable accommodation for an overnight stay. The following morning, I took the MS Helgoland by Cassen Eils, which is slower but cheaper than the other ferries you can choose from – I paid €74 for the return trip, plus €6 for a second piece of luggage. This boat is slower than the others, so the journey takes a bit longer. This allows you to get better views of seabirds on the way – well worth it! The MS Helgoland is also more resistant to bad weather – the other ferries quickly get cancelled in stormy weather. The 2.5-hour ferry trip to Helgoland was disappointingly uneventfull, with Black-headed, Common, and Herring Gulls, Black-legged Kittiwake, Common Tern, Great Cormorant, and an unidentified skua.

Upon getting off the boat, I was greeted by a large number of Willow Warblers and Northern Wheatears litterally everywhere in the harbour area and was excited at the thought of such masses of birds being a daily thing. As I navigated my way through the unfamiliar labyrinth of alleys in the town, I realized that I did not know anything about the setting at the observatory – who else works there, what the work is like, and how the whole atmosphere is. I was welcomed by Lukas, who showed me around and with whom I also shared a room during my stay. Soon after, I met all of the other members of the roughly 15-person group, many of whom, like Lukas, were doing a voluntary ecological year. A group of BSc, MSc, and one PhD students were working on a project on the effects of electromagnetic radiation on the direction of migration of Northern Wheatears. I learned more about their research during my stay by being shown the experiment set-up and participating in some of the steps, which was all very interesting.

I was immediately involved in the work by participating in the afternoon’s first trapping session, as I will call it here. The German term is “Fangtrieb”, which when I translated it on Google Translate gave me “catching instinct”! Surely not correct – or is it? At hourly intervals during the day apart from a three-hour midday break, birds are trapped in the observatory’s garden housing the famous Helgoland traps. This system constitutes of large nets which funnel flying birds into a small enclosure and box, from where they can be removed for ringing. To drive the birds into the boxes at the end, several people simultaneously run in a coordinated manner along a system of paths that lead into one trap and then onto the next, for a total of three traps. Subsequently, the birds are brought to the adjacent ringing hut, where they are ringed and data is collected on their fat and muscle scores (important indicators during migration), as well as weight and size indices.

Being introduced to ringing work was very interesting as I had been curious about this for a long time. The people ringing the birds were very experienced, while volunteers were also learning the handling under supervision. Initially, I mainly watched the others and was then introduced to the proper grips for handling the birds. Throughout my stay I improved significantly since it requires quite some practice to get a feel for handling the birds correctly. Learning this was primarily impeded by the small number of birds we often caught, meaning that I could not try out as much as I’d have liked to – I lament more (too much?) about the often suboptimal migration conditions in my next post. Nonetheless, halfway through my time on the island I was allowed to ring my first bird (a Common Redstart, the most common birds we caught, but very cool nonetheless), and by the end I had ringed various birds and felt very comfortable with the handling. Some days, we also opened two mist nets on the the observatory property, which resulted in more birds.

This work takes priority over other responsibilities, ensuring that trapping occurs in a consistent manner. In between, we worked mainly on keeping the garden and observatory organised and clean, with the outside areas requiring particular effort to be kept clear of weeds, as well as the digitalisation of historical data into the observatory’s database. The latter is somewhat of a Sisyphean task – during my time there, I only managed to enter data on a particular House Sparrow project over two years in the 1970s. Fortunately nowadays the ringing data is recorded digitally, partly in another important routine at the observatory: The “ornithological diary”. This serves to record all bird sightings all members logged across the island on the previous day. This was stressful for the first few days – a bird list is rapidly read out and people call out the number, age, and sex of the birds they recorded. Having an ordered list of personal sightings ready at the is handy, as I soon learnt.

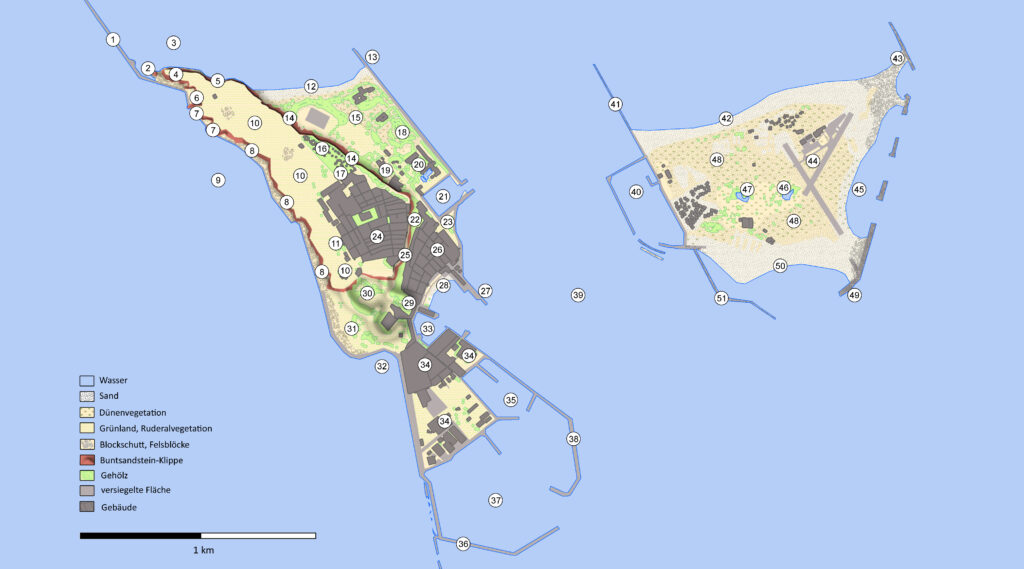

The locations noted in this post follow the names given in the observatory map (below). This map is from the OAG Helgoland, which displays information on each of the numbered points on the map (read here).

When not doing observatory work, in other words during lunch break, before and after work, we went out birding (surprise!). We often did this alone or in small groups, meaning that most days the entire main island (and sometimes the Düne, the smaller island) was covered. This was great as often specials found at one side were immediately shared, allowing everyone interested to join.

On the first days, I paid a few visits to the Northern Gannet colony at the Western cliff. This is one of Helgoland’s ornithological highlights, although by this time of year few gannets were still present, while the kittiwakes, razorbills, guillemots and fulmars also breeding there in summer had already left. Nonetheless, the relentless activity in the colony and the close proximity to the birds always made for amusing encounters. Like everyone else at the observatory though, I quickly lost interest as the interest for rare migrants took over.

The “Oberland” is a good place for resting European Golden Plovers early in the morning, as well as Common Snipe, Meadow and Tree Pipits, Whinchat, and Northern Wheatear. I also found a Eurasian Wryneck on a fence post, a few days after having seen my first ever wryneck at the North-Eastern beach. Both sightings were exciting because this was a species I had wanted to see for years. The group seemed to be a bit of a “nemesis genus” for me, having failed to see its red-throated cousin in South Africa despite birding in the right habitat many times. Eurasian Sparrowhawks, which at times appeared to be the most common species on the island (we caught several a day on some days, occasionally with a songbird still in the talons) could be observed hunting here. Eurasian Hobby and Peregrine Falcon were seen a few times from here as well. The highlight here were sightings of Short-eared Owl, quartering low over the grassland on several evenings.

The North-Eastern beach was often very productive and waders often allowed a very close approach. Ruddy Turnstone, Dunlin, Sanderling, Red Knot, Common Ringed Plover, European Golden Plover, Eurasian Oystercatcher and Bar-tailed Godwit were present every day, Ruff and Little Stint much more rarely. In addition to waders, Northern Wheatear, White and Western Yellow Wagtails, Meadow Pipit, and Eurasian Linnet were also common along the beach and in the dunes, while Common and Sandwich Terns flew overhead. Common Eider, Common Guillemot, and Razorbill were ever-present, the latter two sometimes quite close to the shore. Some individuals – unfortunately likely with bird flu, which had devasting effects on their populations – were also regularly seen resting on the beaches or piers around the island. I also gave sea-watching a shot from this area a few times, which delivered Arcitc Skua, Red-throated Diver, Common Scoter, Canada, Greylag and Brent Geese, and Northern Fulmar.

The North-East area adjacent to the beach and extending south to the compost pile (Google Maps location), was probably my favourite area for birding. Great Spotted Woodpecker, Willow Warbler, Common and Lesser Whitethroats, Eurasian Blackcap, Garden Warbler, Common Redstart, European Robin and Great and Blue Tits were usually common here. Eurasian Siskin often flew past, and in addition to Barn Swallow and Common House-Martin, Common Swift was sometimes hawking insects overhead as well. The bushes between the compost and football pitch were very productive, producing three nice Phylloscopus warblers: Yellow-browed and Greenish Warblers, and Iberian Chiffchaff. Grey Wagtail was often present at the compost as well. The “Kurpark” South-East of the North-East area usually held similar species.

Another excellent area is the ridge between the “Mittelland” and “Kringel”. This was in fact the favourite area for some at the observatory as you can look down into the vegetation of the Mitteland on one side and the barren Kringel on the other, and have excellent views over the sea in the West, to the Düne to the East, and the harbour area to the South. One of the highlights here for me was a striking male Red-breasted Flycatcher. Lukas had heard this extremely skulking bird calling from the trees of the Mittelland and several of us tried to see it in the waning evening light. I happened to be in the right place at it perched on a branch deep within the thicket for a split-second. Northern Pintail, Common Cuckoo, migrating Western Marsh-Harriers, a tame Eurasian Wryneck (the third), and an Ortolan Bunting were nice sightings in this area, while all of the redstarts, warblers, blackcaps, and whitethroats that abounded in the North-East area were also very common here, as were Eurasian Wren and Dunnock.

One of Helgoland’s classic autumn migrants, Yellow-browed Warbler, also arrived. Jacob, who was also volunteering for roughly a month, and I eventually also heard an individual at the lighthouse, and others from the observatory located it soon after. This was a lifer for me, and a very cute bird too. The lighthouse area was quite promising in general, with Whinchats being particularly common, and Common Starlings on the lighthouse. The barren area here is apparently also good for various rarities, although it is lighthouse property and off-limits.

Of course, Helgoland is famous as a rarities hotspot and while September is generally not as exciting as October in this regard, some great things were recorded when I was there. The most nerve-wracking seconds often occurred in the common room of the observatory. As we were eating breakfast or lunch, a notification from the Helgoland rarities group left all of our phones ringing and buzzing (most people had unique ringtones for this group, so there could be no mistake). A scramble ensued for those who had their phones nearby, while the others tensed up as someone broke the suspense by sharing the news. Often this constituted updates of previously-found birds or sightings of not very special birds, but sometimes, the messages caused minor havocs.

One such moment occurred one morning after breakfast: A Rustic Bunting at the compost heap in the North-East area. We ran. As we got to the site, we heard the distinctive “tic” call that indicates buntings that are rare on Helgoland (particulary Little Buntings are often located by this call). With a small group of twichers that had gathered, we soon had good views of a Rustic Bunting, which was usually either in a thicket or flying around. This sighting reminded me of the scene in the movie The Big Year, when a Rustic Bunting is reported on the Aleutan island of Attu. As we watched the bunting, a Yellow-browed Warbler hopped onto the same branch on which the bunting sat a few seconds earlier, but nobody really cared. The Rustic Bunting was only infrequently seen for a few days but I had an unbeatable sighting together with Fynn, who volunteers at the observatory for a year, as it perched on a dead bush just meters from us.

Once every few days, the news of a raptor flying over the island would interrupt our (often already hasty) lunch. A comic scene ensued as everyone grabbed their binoculars, crowded the window or stood on chairs with the hope of glimpsing the passing bird. European Honey-Buzzard was the most common, although Western Marsh-Harriers and Common Buzzards also migrated through. One early evening, as we chatted in the common room (I forgot the topic but it was undoubtedly something along the lines of distinguishing features between Arctic, Pomarine, and Long-tailed Skuas), a Pallid Harrier was seen on the Oberland. Several of us ran outside and were rewarded with a brief fly-by of the bird. We then ran around along the Western cliffs as the harrier somehow appeared and disappeared randomly, much to the amusement of some tourists. The chase was briefly abandoned to watch an Osprey majestically migrate through and head away over the sea. As the harrier reappeared, another Osprey suddenly showed up and flew along the red cliffs wing to wing with the harrier! The latter flew off but we head another good view of the Osprey before we decided to call it a day, happily realizing that it could not get much better.

The South harbour area is interesting because of its position on the southern tip of the island, with this being the final stop before birds continue their migration. Unfortunately, there is not as much open habitat remaining as there used to, but I still saw Common Redshank, Little Stint (including a ringed individual was ringed 15 days earlier nearly 900km north in Norway), and the common grassland birds on Helgoland. The typical Barn Swallow and Common House Martin were also common here, and Sand Martin also put in an appearance. The small beach by the Kringel was also good for gulls, often had Carrion Crow and Eurasian Jackdaw, and Common Sandpipers often foraged along the water. Particularly after storms, the Southwestern pier is great for gulls – I saw Black-headed, Common, Lesser Black-backed, Great Black-backed, and Herring Gulls, as well as Black-legged Kittiwake. In the harbour, Razorbill, Common Guillemot, Common Eider, and Great Cormorant were common.

The observatory itself was quite productive as well, with the main interesting species during my time here being an Iberian Chiffchaff (the same as I noted earlier in the North-East area). This bird was calling every day but I only got good views once as it was very secretive. After one trapping session, I walked back towards the ringing hut when I saw a flutter and a stunning Red-breasted Flycatcher perched right in front of me. We managed to trap this bird subsequently, which got everone from the observatory to crowd into the ringing hut. I also found a Wood Warbler in the observatory garden, and we also had good sightings of Common Cuckoo, Fieldfare, Mistle Thrush, and Red Crossbill, in addition to the many common birds like Firecrest and Goldcrest.

I paid two visits to the Düne in the first two weeks. The ferry leaves every half hour (although this is season-dependent!), so one could be quite flexible. A tourist return ticket costs €6. The small Düne harbour is a good place for Black Guillemot. The Northern beach is, similar to the main island’s North-Eastern beach, excellent for waders and I saw all of the typical species as well as Eurasian Curlew. An evening visit to the beach with Jacob and Fynn produced an Arctic Skua flying above us. Another attraction are the Grey and Harbour Seals that rest on the beach here. The scrubby central part of the Düne is good for many of the passerines seen on the main island as well, and Common Starling, Eurasian Magpie, and Common Kestrel are obvious here. The two ponds revealed a Eurasian Wigeon, Eurasian Teal, Mallard, Common Moorhen. A Common Kingfisher here was twitched by many at the observatory since it’s a rare bird on Helgoland.

The first two weeks went by fast and delivered many good sightings. At times the birding was slow however, which a bit disappointing knowing that September often brings many more special birds. However, I was exceedingly happy to be in the company of similarly-aged birders with whom I also got along perfectly in general. The second half of my stay proved to be even more successful (read here).

3 thoughts on “Helgoland (Part I), 01.09.-17.09.2023”